MIT spinout seeks to transform food safety testing

An affordable, easy-to-use handheld sensor, soon to enter the market, can indicate the presence of bacterial contaminants in food in seconds.

“This is a $10 billion market and everyone knows it.” Those are the words of Chris Hartshorn, CEO of a new MIT spinout — Xibus Systems — that is aiming to make a splash in the food industry with their new food safety sensor.

Hartshorn has considerable experience supporting innovation in agriculture and food technology. Prior to joining Xibus, he served as chief technology officer for Callaghan Innovation, a New Zealand government agency. A large portion of the country’s economy relies upon agriculture and food, so a significant portion of the innovation activity there is focused on those sectors.

While there, Hartshorn came in contact with a number of different food safety sensing technologies that were already on the market, aiming to meet the needs of New Zealand producers and others around the globe. Yet, “every time there was a pathogen-based food recall” he says, “it shone a light on the fact that this problem has not yet been solved.”

He saw innovators across the world trying to develop a better food pathogen sensor, but when Xibus Systems approached Hartshorn with an invitation to join as CEO, he saw something unique in their approach, and decided to accept.

Novel liquid particles provide quick indication of food contamination

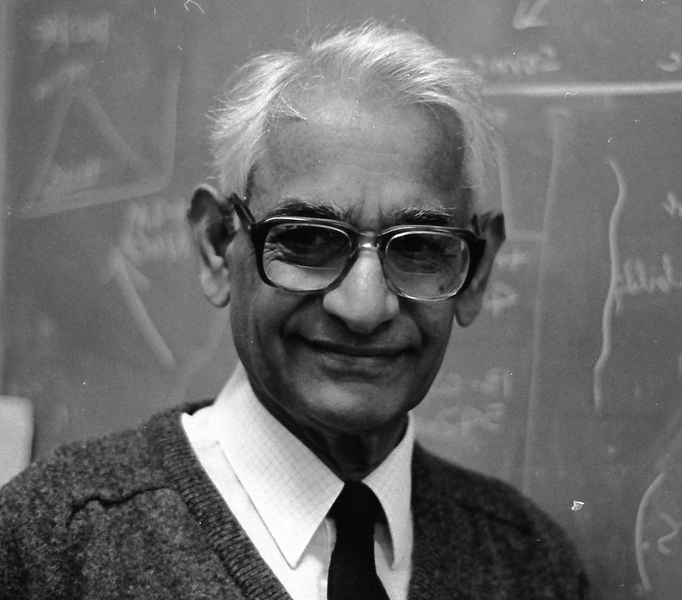

Xibus Systems was formed in the fall of 2018 to bring a fast, easy, and affordable food safety sensing technology to food industry users and everyday consumers. The development of the technology, based on MIT research, was supported by two commercialization grants through the MIT Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Lab’s J-WAFS Solutions program. It is based on specialized droplets — called Janus emulsions — that can be used to detect bacterial contamination in food. The use of Janus droplets to detect bacteria was developed by a research team led by Tim Swager, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Chemistry, and Alexander Klibanov, the Novartis Professor of Biological Engineering and Chemistry.

Swager and researchers in his lab originally developed the method for making Janus emulsions in 2015. Their idea was to create a synthetic particle that has the same dynamic qualities as the surface of living cells.

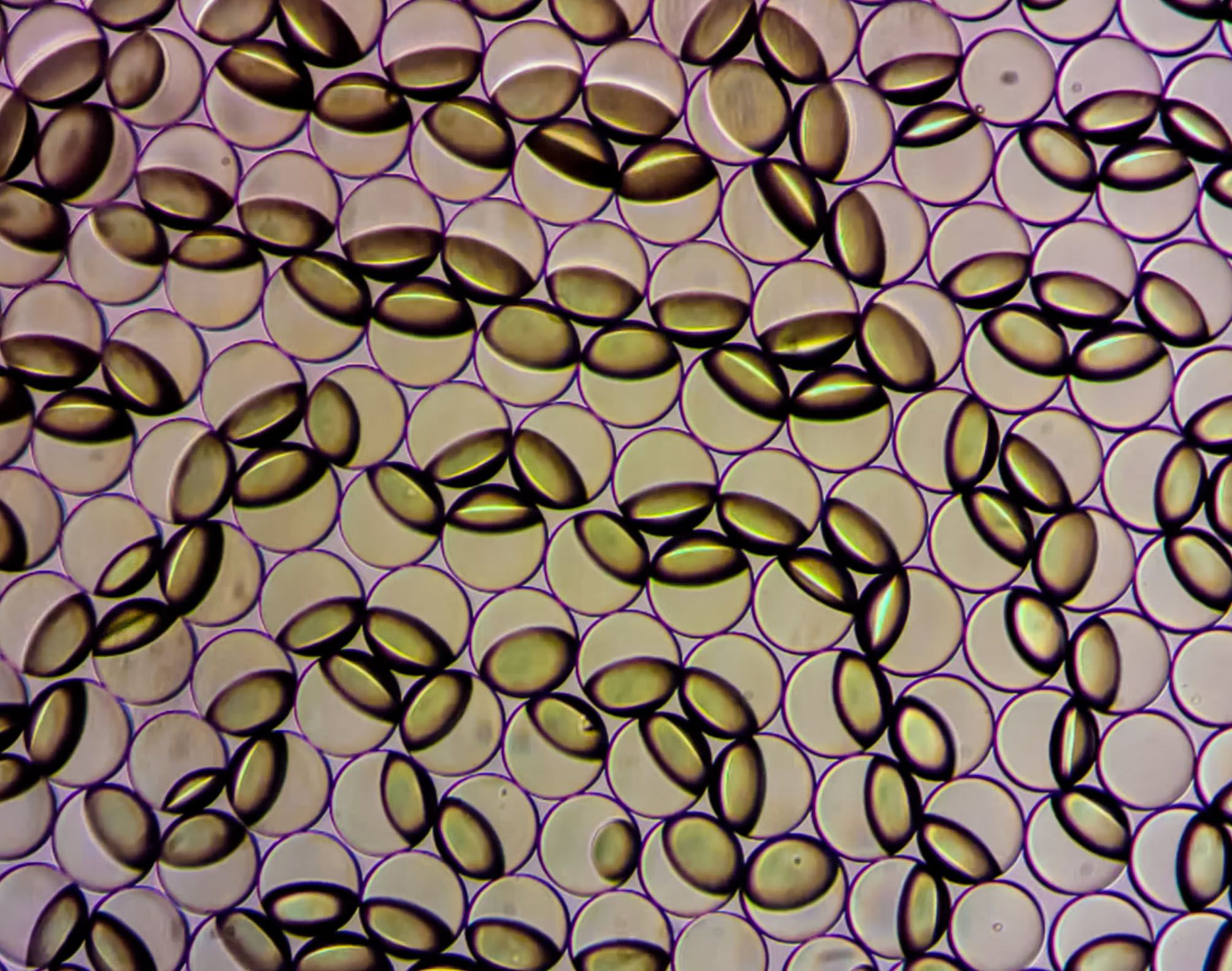

The liquid droplets consist of two hemispheres of equal size, one made of a blue-tinted fluorocarbon and one made of a red-tinted hydrocarbon. The hemispheres are of different densities, which affects how they align and how opaque or transparent they appear when viewed from different angles. They are, in effect, lenses. What makes these micro-lenses particularly unique, however, is their ability to bind to specific bacterial proteins. Their binding properties enabled them to move, flipping from a red hemisphere to blue based on the presence or absence of a particular bacteria, like Salmonella.

“We were thrilled by the design,” Swager says. “It is a completely new sensing method that could really transform the food safety sensing market. It showed faster results than anything currently available on the market, and could still be produced at very low cost.”

Janus emulsions respond exceptionally quickly to contaminants and provide quantifiable results that are visible to the naked eye or can be read via a smartphone sensor.

“The technology is rooted in very interesting science,” Hartshorn says. “What we are doing is marrying this scientific discovery to an engineered product that meets a genuine need and that consumers will actually adopt.”

Having already secured nearly $1 million in seed funding from a variety of sources, and also being accepted into Sprout, a highly respected agri-food accelerator, they are off to a fast start.

Solving a billion-dollar industry challenge

Why does speed matter? In the field of food safety testing, the standard practice is to culture food samples to see if harmful bacterial colonies form. This process can take many days, and often can only be performed offsite in a specialized lab.

While more rapid techniques exist, they are expensive and require specialized instruments — which are not widely available — and still typically require 24 hours or more from start to finish. In instances where there is a long delay between food sampling and contaminant detection, food products could have already reached consumers hands — and upset their stomachs. While the instances of illness and death that can occur from food-borne illness are alarming enough, there are other costs as well. Food recalls result in tremendous waste, not only of the food products themselves but of the labor and resources involved in their growth, transportation, and processing. Food recalls also involve lost profit for the company. North America alone loses $5 billion annually in recalls, and that doesn’t count the indirect costs associated with the damage that occurs to particular brands, including market share losses that can last for years.

The food industry would benefit from a sensor that could provide fast and accurate readings of the presence and amount of bacterial contamination on-site. The Swager Group’s Janus emulsion technology has many of the elements required to meet this need and Xibus Systems is working to improve the speed, accuracy, and overall product design to ready the sensor for market.

Two other J-WAFS-funded researchers have helped improve the efficiency of early product designs. Mathias Kolle, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT and recipient of a separate 2017 J-WAFS seed grant, is an expert on optical materials. In 2018, he and his graduate student Sara Nagelberg performed the calculations describing light’s interaction with the Janus particles so that Swager’s team could modify the design and improve performance. Kolle continues to be involved, serving with Swager on the technical advisory team for Xibus.

This effort was a new direction for the Swager group. Says Swager: “The technology we originally developed was completely unprecedented. At the time that we applied to for a J-WAFS Solutions grant, we were working in new territory and had minimal preliminary results. At that time, we would have not made it through, for example, government funding reviews which can be conservative. J-WAFS sponsorship of our project at this early stage was critical to help us to achieve the technology innovations that serve as the foundation of this new startup.”

Xibus co-founder Kent Harvey — also a member of the original MIT research team—is joined by Matthias Oberli and Yuri Malinkevich. Together with Hartshorn they are working on a prototype for initial market entry. They are actually developing two different products: a smartphone sensor that is accessible to everyday consumers, and a portable handheld device that is more sensitive and would be suitable for industry. If they are able to build a successful platform that meets industry needs for affordability, accuracy, ease of use, and speed, they could apply that platform to any situation where a user would need to analyze organisms that live in water. This opens up many sectors in the life sciences, including water quality, soil sensing, veterinary diagnostics, as well as fluid diagnostics for the broader healthcare sector.

The Xibus team wants to nail their product right off the bat.

“Since food safety sensing is a crowded field, you only get one shot to impress your potential customers,“ Hartshorn says. “If your first product is flawed or not interesting enough, it can be very hard to open the door with these customers again. So we need to be sure our prototype is a game-changer. That’s what’s keeping us awake at night.”