Artifacts from a half-century of cancer research

Ten objects on display in the Koch Institute Public Galleries offer uncommon insights into the people and progress of MIT's cancer research community.

Throughout 2024, MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research has celebrated 50 years of MIT’s cancer research program and the individuals who have shaped its journey. In honor of this milestone anniversary year, on Nov. 19 the Koch Institute celebrated the opening of a new exhibition: Object Lessons: Celebrating 50 Years of Cancer Research at MIT in 10 Items.

Object Lessons invites the public to explore significant artifacts — from one of the earliest PCR machines, developed in the lab of Nobel laureate H. Robert Horvitz, to Greta, a groundbreaking zebra fish from the lab of Professor Nancy Hopkins — in the half-century of discoveries and advancements that have positioned MIT at the forefront of the fight against cancer.

50 years of innovation

The exhibition provides a glimpse into the many contributors and advancements that have defined MIT’s cancer research history since the founding of the Center for Cancer Research in 1974. When the National Cancer Act was passed in 1971, very little was understood about the biology of cancer, and it aimed to deepen our understanding of cancer and develop better strategies for the prevention, detection, and treatment of the disease. MIT embraced this call to action, establishing a center where many leading biologists tackled cancer’s fundamental questions. Building on this foundation, the Koch Institute opened its doors in 2011, housing engineers and life scientists from many fields under one roof to accelerate progress against cancer in novel and transformative ways.

In the 13 years since, the Koch Institute’s collaborative and interdisciplinary approach to cancer research has yielded significant advances in our understanding of the underlying biology of cancer and allowed for the translation of these discoveries into meaningful patient impacts. Over 120 spin-out companies — many headquartered nearby in the Kendall Square area — have their roots in Koch Institute research, with nearly half having advanced their technologies to clinical trials or commercial applications. The Koch Institute’s collaborative approach extends beyond its labs: principal investigators often form partnerships with colleagues at world-renowned medical centers, bridging the gap between discovery and clinical impact.

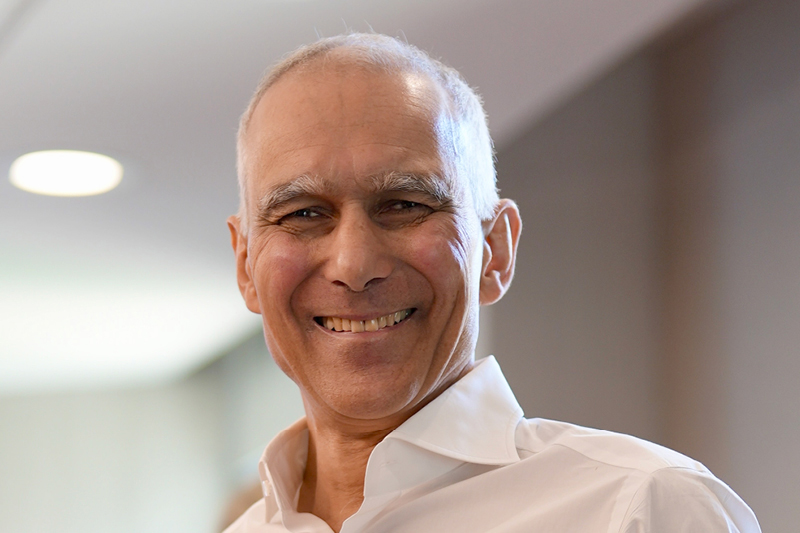

Current Koch Institute Director Matthew Vander Heiden, also a practicing oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, is driven by patient stories.

“It is never lost on us that the work we do in the lab is important to change the reality of cancer for patients,” he says. “We are constantly motivated by the urgent need to translate our research and improve outcomes for those impacted by cancer.”

Symbols of progress

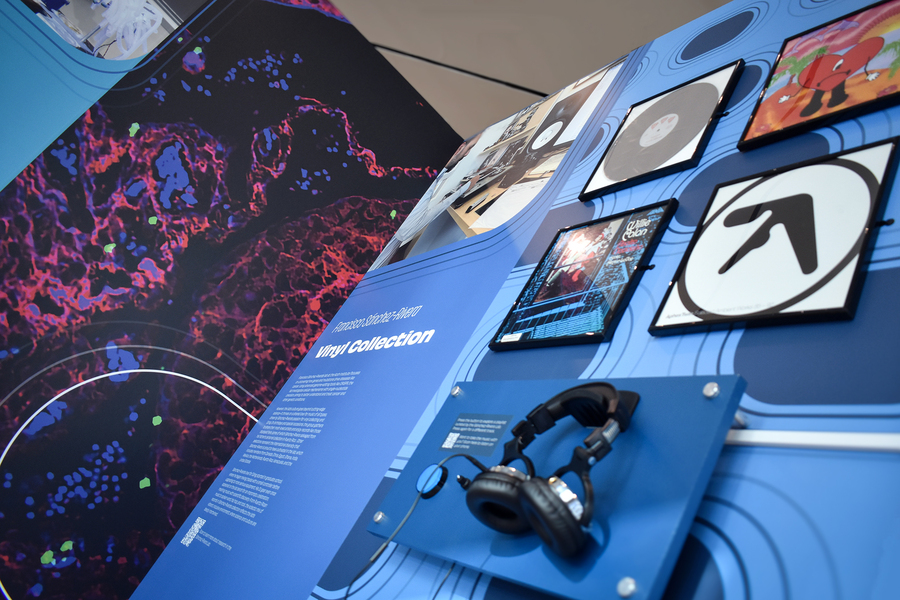

The items on display as part of Object Lessons take viewers on a journey through five decades of MIT cancer research, from the pioneering days of Salvador Luria, founding director of the Center for Cancer Research, to some of the Koch Institute’s newest investigators, including Francisco Sánchez-Rivera, the Eisen and Chang Career Development Professor and an assistant professor of biology, and Jessica Stark, the Underwood-Prescott Career Development Professor and an assistant professor of biological engineering and chemical engineering.

Among the standout pieces is a humble yet iconic object: Salvador Luria’s ceramic mug, emblazoned with “Luria’s broth.” Lysogeny broth, often called — apocryphally — Luria Broth, is a medium for growing bacteria. Still in use today, the recipe was first published in 1951 by a research associate in Luria’s lab. The artifact, on loan from the MIT Museum, symbolizes the foundational years of the Center for Cancer Research and serves as a reminder of Luria’s influence as an early visionary. His work set the stage for a new era of biological inquiry that would shape cancer research at MIT for generations.

Visitors can explore firsthand how the Koch Institute continues to build on the legacy of its predecessors, translating decades of knowledge into new tools and therapies that have the potential to transform patient care and cancer research.

For instance, the PCR machine designed in the Horvitz Lab in the 1980s made genetic manipulation of cells easier, and gene sequencing faster and more cost-effective. At the time of its commercialization, this groundbreaking benchtop unit marked a major leap forward. In the decades since, technological advances have allowed for the visualization of DNA and biological processes at a much smaller scale, as demonstrated by the handheld BioBits imaging device developed by Stark and on display next door to the Horvitz panel.

“We created BioBits kits to address a need for increased equity in STEM education,” Stark says. “By making hands-on biology education approachable and affordable, BioBits kits are helping inspire and empower the next generation of scientists.”

While the exhibition showcases scientific discoveries and marvels of engineering, it also aims to underscore the human element of cancer research through personally significant items, such as a messenger bag and Seq-Well device belonging to Alex Shalek, J. W. Kieckhefer Professor in the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science and the Department of Chemistry.

Shalek investigates the molecular differences between individual cells, developing mobile RNA-sequencing devices. He could often be seen toting the bag around the Boston area and worldwide as he perfected and shared his technology with collaborators near and far. Through his work, Shalek has helped to make single-cell sequencing accessible for labs in more than 30 countries across six continents.

“The KI seamlessly brings together students, staff, clinicians, and faculty across multiple different disciplines to collaboratively derive transformative insights into cancer,” Shalek says. “To me, these sorts of partnerships are the best part about being at MIT.”

Around the corner from Shalek’s display, visitors will find an object that serves as a stark reminder of the real people impacted by Koch Institute research: Steven Keating’s SM ’12, PhD ’16 3D-printed model of his own brain tumor. Keating, who passed away in 2019, became a fierce advocate for the rights of patients to their medical data, and came to know Vander Heiden through his pursuit to become an expert on his tumor type, IDH-mutant glioma. In the years since, Vander Heiden’s work has contributed to a new therapy to treat Keating’s tumor type. In 2024, the drug, called vorasidenib, gained FDA approval, providing the first therapeutic breakthrough for Keating’s cancer in more than 20 years.

As the Koch Institute looks to the future, Object Lessons stands as a celebration of the people, the science, and the culture that have defined MIT’s first half-century of breakthroughs and contributions to the field of cancer research.

“Working in the uniquely collaborative environment of the Koch Institute and MIT, I am confident that we will continue to unlock key insights in the fight against cancer,” says Vander Heiden. “Our community is poised to embark on our next 50 years with the same passion and innovation that has carried us this far.”

Object Lessons is on view in the Koch Institute Public Galleries Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., through spring semester 2025.