A step toward a universal flu vaccine

With computer models and lab experiments, researchers are working on a strategy for vaccines that could protect against any influenza virus.

Each year, the flu vaccine has to be redesigned to account for mutations that the virus accumulates, and even then, the vaccine is often not fully protective for everyone.

Researchers at MIT and the Ragon Institute of MIT, MGH, and Harvard are now working on strategies for designing a universal flu vaccine that could work against any flu strain. In a study appearing today, they describe a vaccine that triggers an immune response against an influenza protein segment that rarely mutates but is normally not targeted by the immune system.

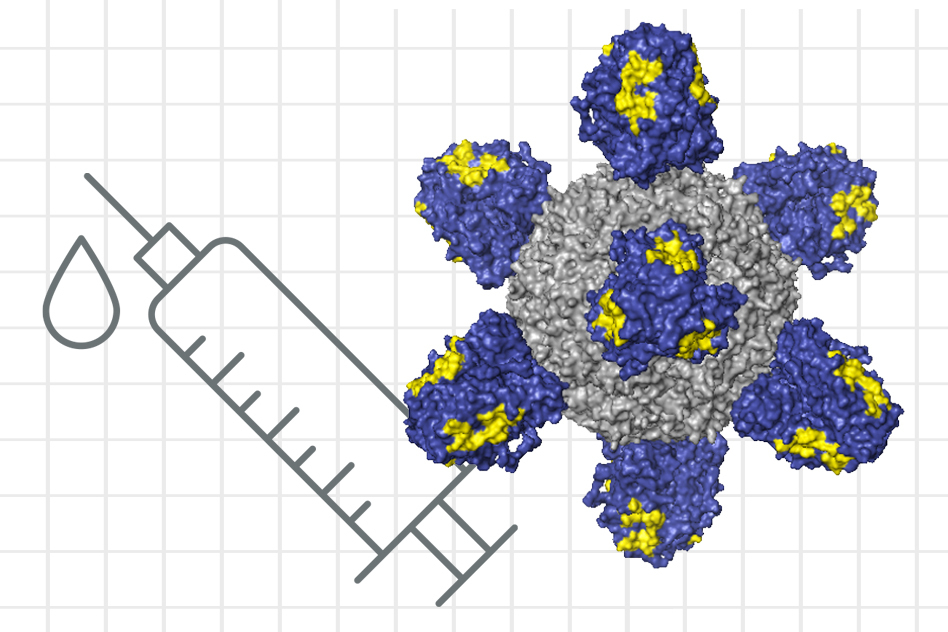

The vaccine consists of nanoparticles coated with flu proteins that train the immune system to create the desired antibodies. In studies of mice with humanized immune systems, the researchers showed that their vaccine can elicit an antibody response targeting that elusive protein segment, raising the possibility that the vaccine could be effective against any flu strain.

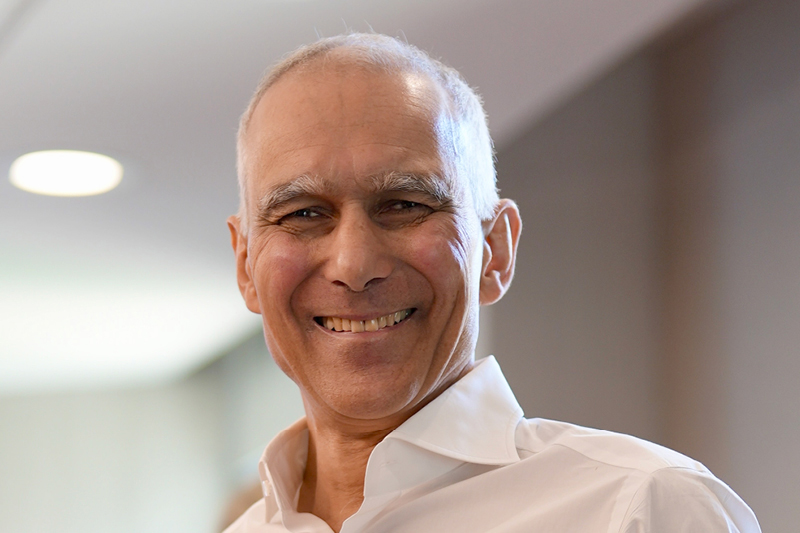

“The reason we’re excited about this work is that it is a small step toward developing a flu shot that you just take once, or a few times, and the resulting antibody response is likely to protect against seasonal flu strains and pandemic strains as well,” says Arup K. Chakraborty, the Robert T. Haslam Professor in Chemical Engineering and professor of physics and chemistry at MIT, and a member of MIT’s Institute for Medical Engineering and Science and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard.

Chakraborty and Daniel Lingwood, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a group leader at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the study, which appears today in Cell Systems. MIT research scientist Assaf Amitai is the lead author of the paper.

Targeting flu

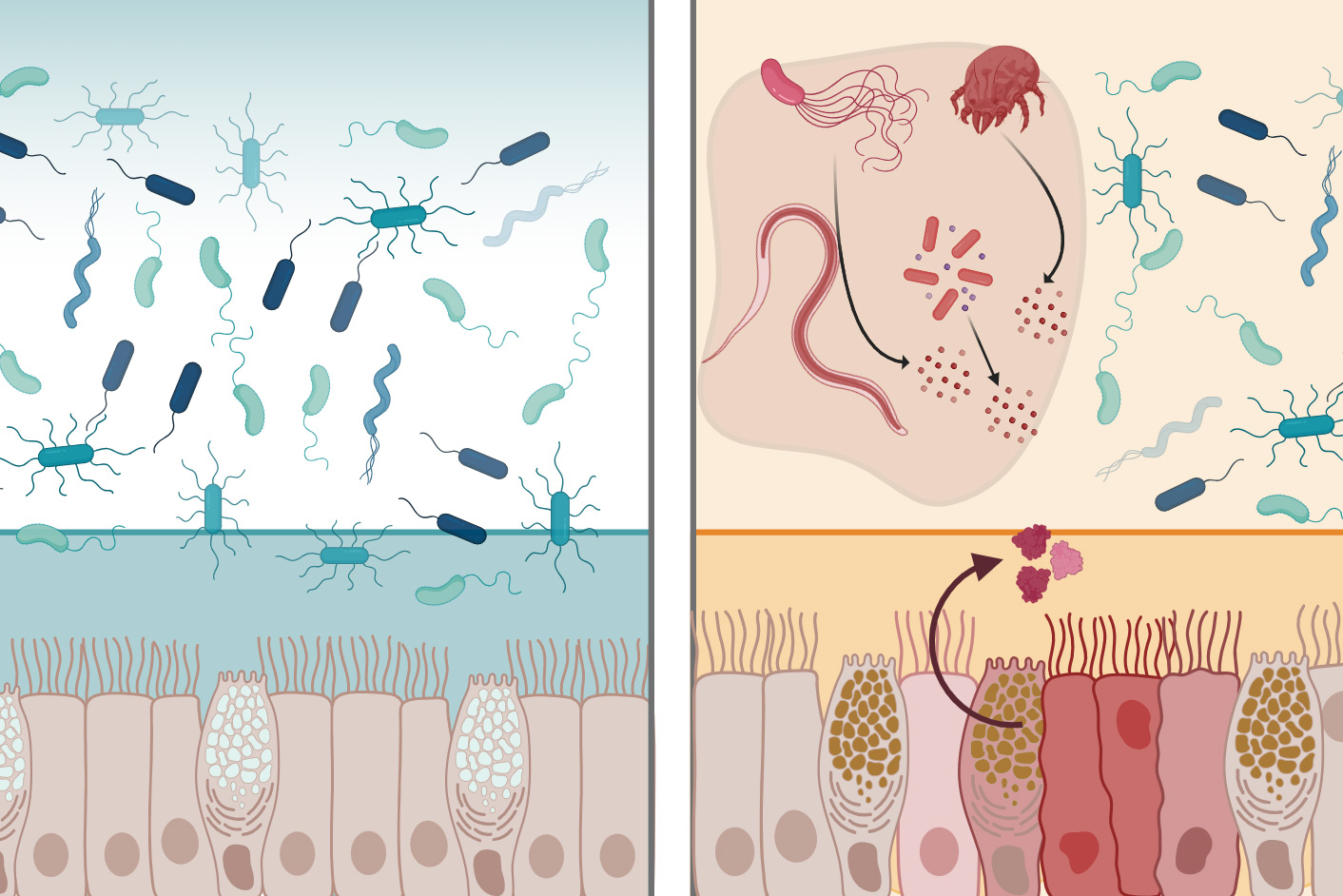

Most flu vaccines consist of inactivated flu viruses. These viruses are coated with a protein called hemagglutinin (HA), which helps them bind to host cells. After vaccination, the immune system generates squadrons of antibodies that target the HA protein. These antibodies almost always bind to the head of the HA protein, which is the part of the protein that mutates the most rapidly. Parts of the HA stem, on the other hand, very rarely mutate.

“We don’t understand the complete picture yet, but for many reasons, the immune system is intrinsically not good at seeing the conserved parts of these proteins, which if effectively targeted would elicit an antibody response that would neutralize multiple influenza types,” Lingwood says.

In their new study, the researchers set out to study why the immune system ends up targeting the HA head rather than the stem, and to find ways to refocus the immune system’s attention on the stem. Such a vaccine could elicit antibodies known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” which would respond to any flu strain. In principle, this kind of vaccine could end the arms race between vaccine designers and rapidly mutating flu viruses.

One factor that was already known to contribute to antibody preference for the HA head is that HA proteins are densely clustered on the surface of the virus, so it’s difficult for antibodies to access the stem region. The head region is much more accessible.

The researchers developed a computational model that helped them to further explore the “immunodominance” of the protein’s head region. “We hypothesized that the surface geometry of the virus could be key to its ability to survive by protecting its vulnerable parts from antibodies,” Amitai says.

The researchers explored the effects of geometry on immunodominance using a technique called molecular dynamics simulation. They further modeled a process called antibody affinity maturation. This process, which occurs after B cells encounter a virus (or a vaccine), determines which antibodies will predominate during the immune response.

Each B cell has on its surface proteins called B cell receptors, which bind to different foreign proteins. Once a particular B cell receptor binds strongly to the HA protein, that B cell becomes activated and starts to multiply rapidly. This process introduces new mutations into the B cell receptors, some of which bind more strongly. These better binders tend to survive, while the weaker binders die. At the end of this process, which takes one or two weeks, there is a population of B cells that is very good at binding strongly to the HA protein. These B cells secrete antibodies that bind to the HA protein.

“As time goes on, after infection, the antibodies get better and better at targeting this particular antigen,” Chakraborty says.

The researchers’ computer simulations of this process revealed that when a typical flu vaccine is given, B cell receptors that bind strongly to the HA stem are at a competitive disadvantage during the maturation process, because they can’t reach their targets as easily as B cell receptors that bind strongly to the HA head.

The researchers also used their computer model to simulate this maturation process with a nanoparticle vaccine developed at the National Institutes of Health, which is now in a phase 1 clinical trial. This particle carries HA stem proteins spaced out at lower density. The model showed that this arrangement makes the proteins more accessible to antibodies, which are Y-shaped, allowing the antibodies to grab onto the proteins with both arms. The simulations revealed that those stem-targeting antibodies predominated at the end of the maturation process.

Refocused immunity

The researchers also used their computational model to predict the outcome of several possible vaccination strategies. One strategy that appears promising is to immunize with an HA stem from a virus that is similar to, but not the same as, strains that the recipient has previously been exposed to. In 2009, many people around the world were either infected with or vaccinated against a novel H1N1 strain. The modeling led the researchers to hypothesize that if they vaccinated with nanoparticles displaying HA-like proteins from a strain that is different from the 2009 version, it should elicit the kind of broadly neutralizing antibodies that may confer universal immunity.

Using mice with human immune cells, the researchers tested this strategy, first immunizing them against the 2009 H1N1 strain, followed by a nanoparticle vaccine carrying the HA stem protein from a different H1N1 strain. They found that this approach was much more successful at eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies than any of the other strategies that they tested.

“We discovered that this particular event in our immune history can actually be harnessed with this particular nanoparticle to refocus the immune system’s attention on one of these so-called universal vaccine targets,” Lingwood says. “When there’s a refocusing event, that means we can swing the antibody response against that target, which under other conditions is simply not seen. We have shown in previous studies that when you’re able to elicit this kind of response, it’s protective against flu strains that mimic pandemic threats.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Harvard University Milton Award, the Gilead Research Scholars Program, and the National Science Foundation Research Fellowship Program.