New snapshots of ancient life

The resolution revolution, beating “blobology”, and shedding light on how ancient microbes thrived in a primordial soup.

A Reflection on Research and Graduate School

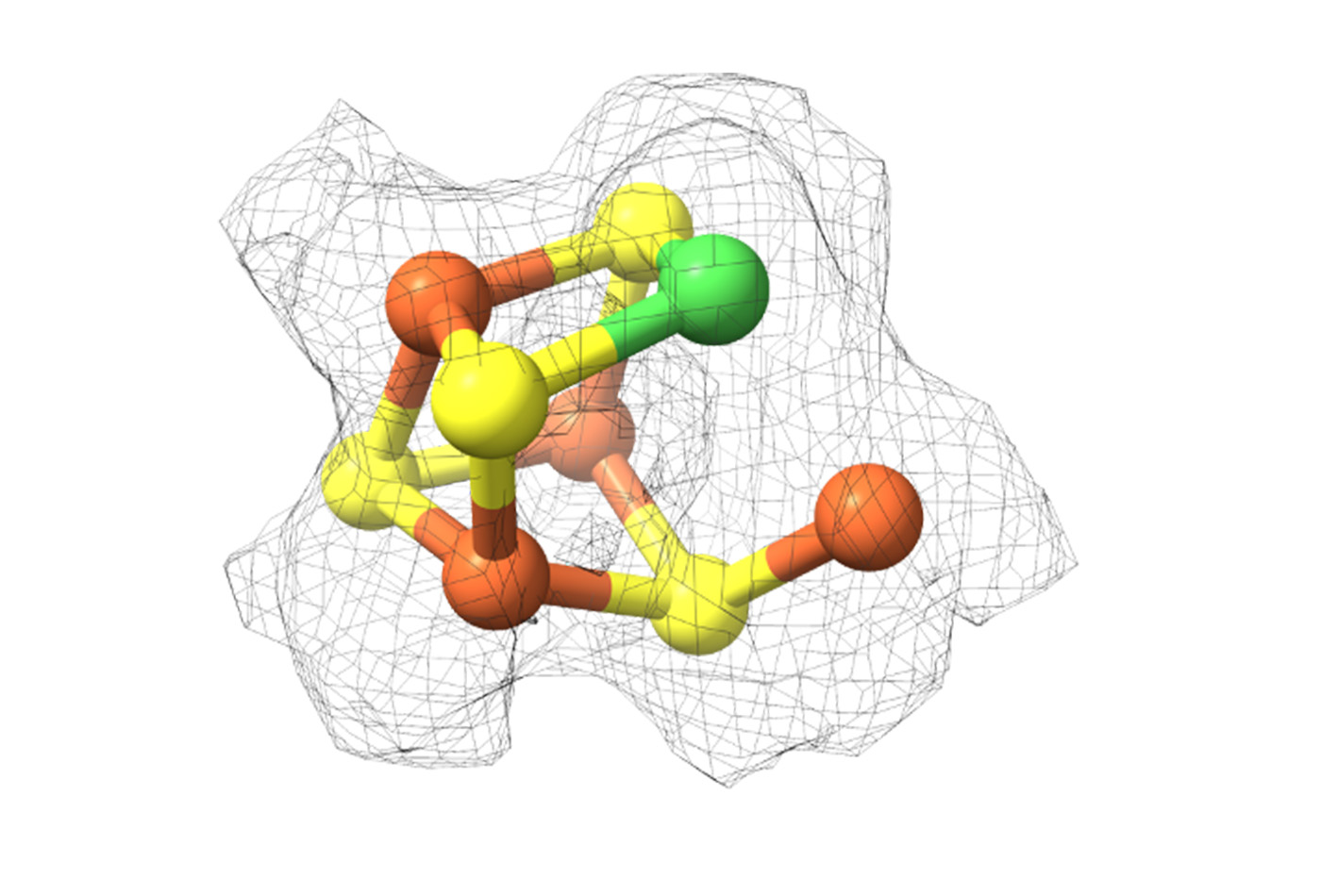

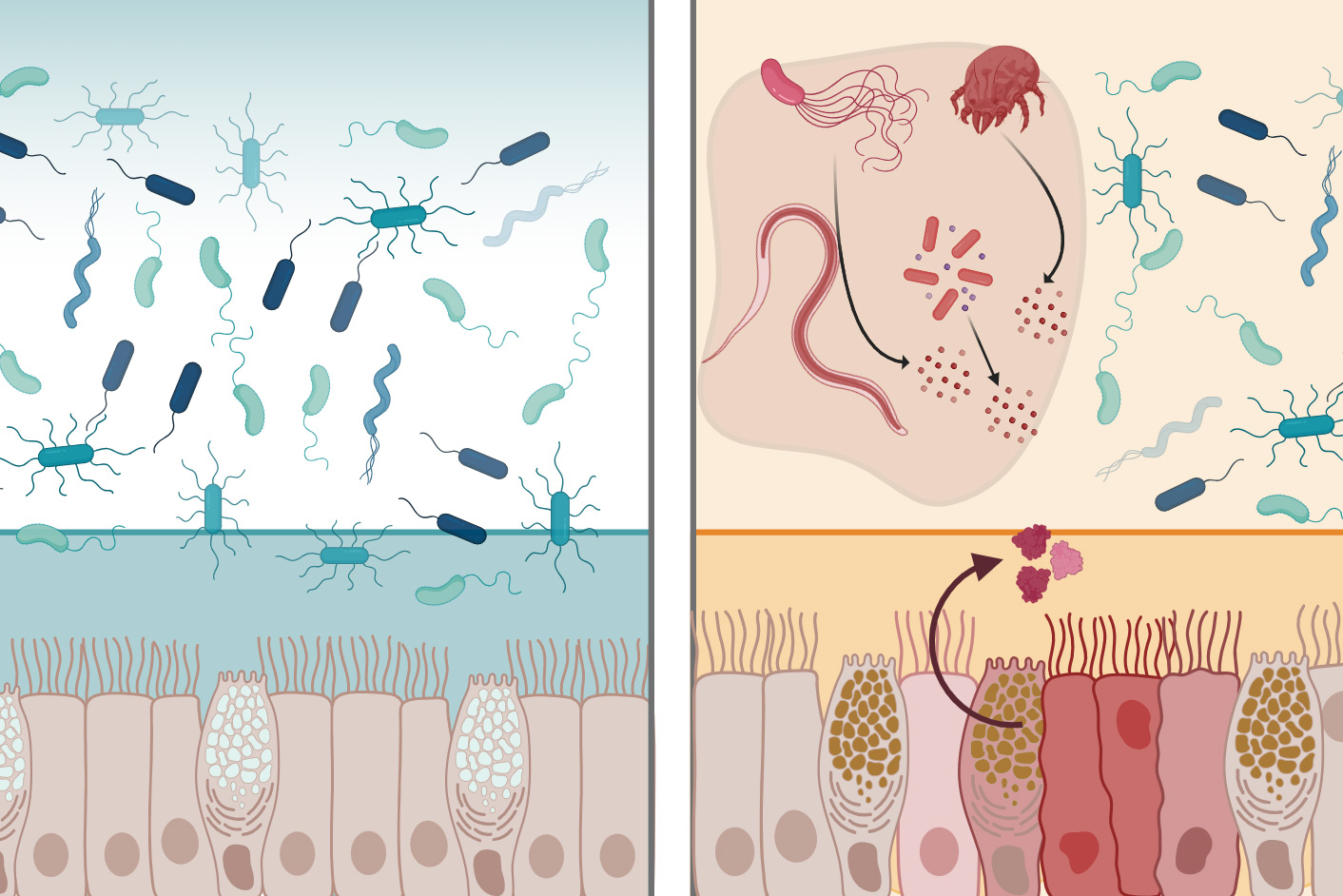

The earliest life on earth created biological molecules despite the limited materials available in the primordial soup such as CO2, hydrogen gas, and minerals containing iron, nickel, and sulfur.

As ancient microbes evolved, they developed proteins that sped up chemical reactions, called enzymes. Enzymes were evolutionarily advantageous because they created local environments called active sites optimized for reaction performance.

Although we know that carbon is the building block of life on earth–we wouldn’t exist without carbon-based molecules such as proteins and DNA–much remains unclear about how more complex carbon-based molecules were originally generated from CO2. Proteins and DNA are huge molecules with thousands of carbon atoms, so creating life from CO2 would be no small undertaking.

Catherine Drennan, Professor of Biology and Chemistry and HHMI Investigator and Professor, has long studied the enzymes that perform these crucial reactions wherein CO2 is converted into a form of carbon that cells can use, which requires iron, nickel, and sulfur.

In particular, she uses structural biology to study carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH), which reacts with CO2 to produce CO, and acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS), which uses CO with another single unit of carbon to create a carbon-carbon bond. Crystallographic work by Drennan and others has provided structural snapshots of bacterial CODH and ACS, but its structure in other contexts remains elusive. During my PhD, I worked with Drennan on the structural characterization of CODH and ACS, culminating in a publication in PNAS, published October 3, 2024.

Throughout Drennan’s career, the lab has used a method known as X-ray crystallography to determine enzyme structures at atomic resolution. In recent years, however, cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has risen in popularity as a structural biology technique.

Cryo-EM offers some key advantages over X-ray crystallography, such as its ability to capture structures of large and dynamic complexes. However, cryo-EM is limited in its ability to elucidate structures of small proteins, an area where X-ray crystallography continues to excel.

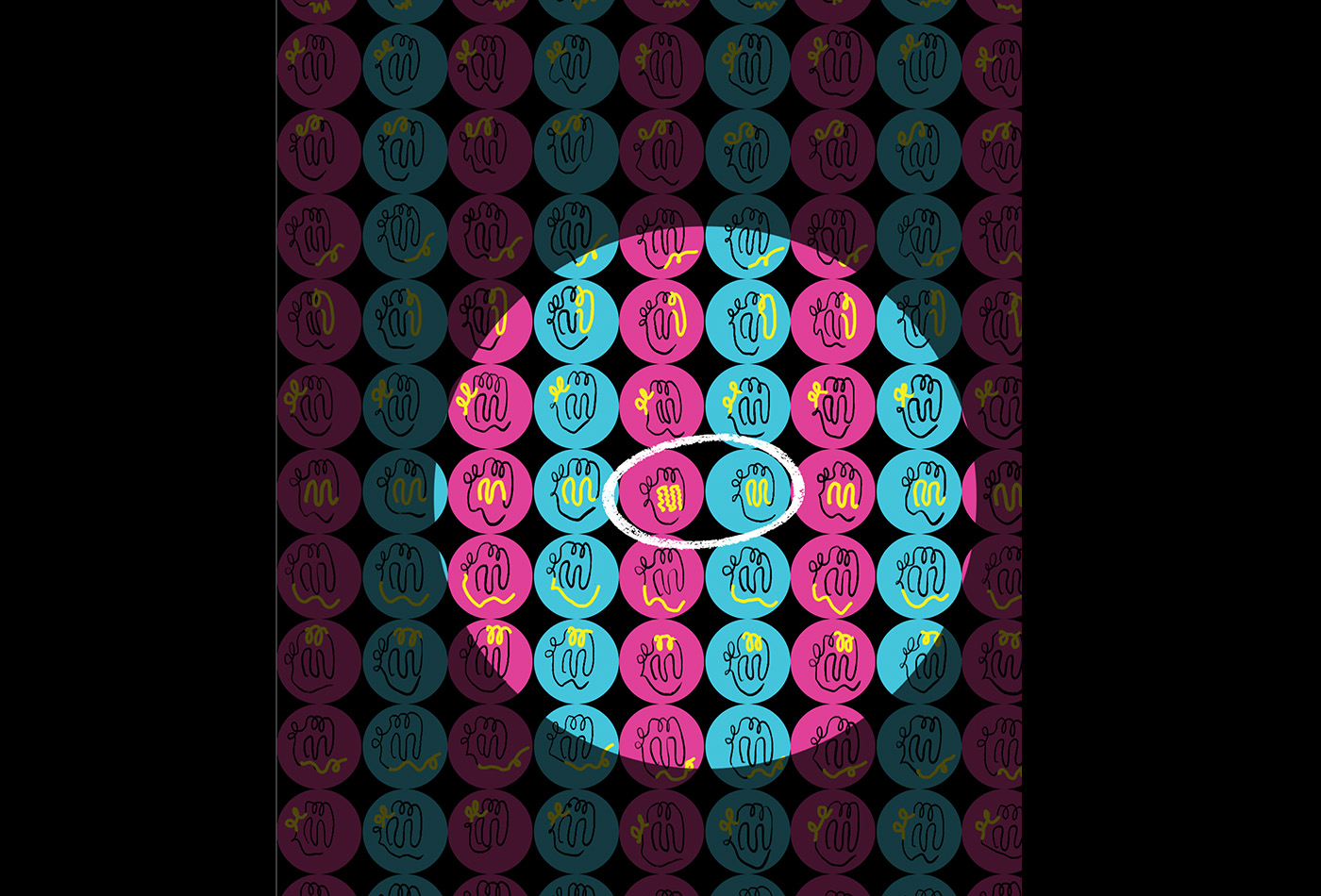

To perform a cryo-EM experiment, proteins are rapidly frozen in a thin layer of ice and imaged on an electron microscope. By capturing images of the protein in various orientations, researchers can generate a 3D model of their protein of interest.

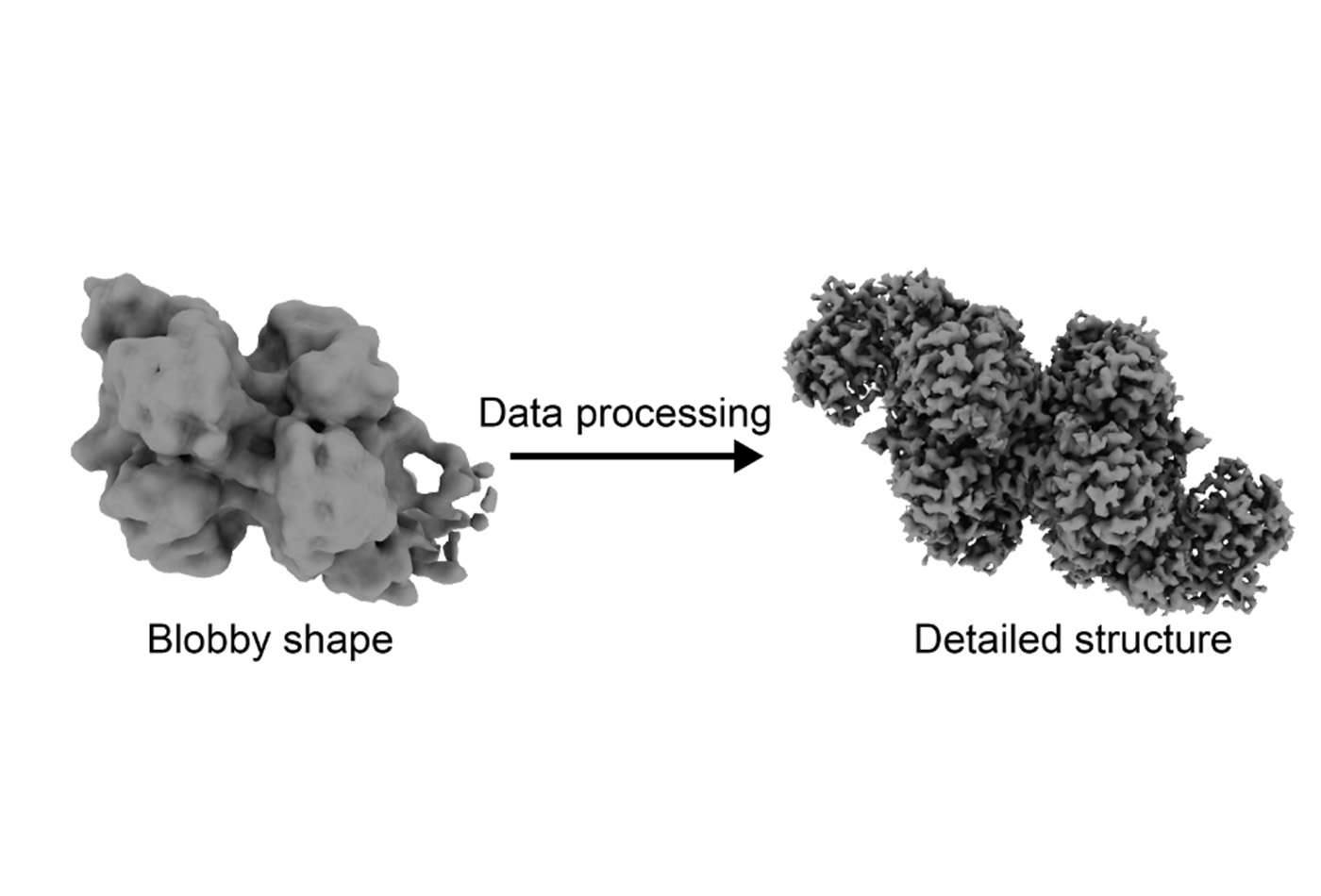

Around 2015, cryo-EM reached a tipping point known as the “resolution revolution.” Due to improvements in both the hardware for collecting cryo-EM data and the software used for data processing, the technique could, for the first time, be used to determine protein structures at near-atomic resolution.

Seeing the potential for this new technique, MIT opened its very own cryo-EM facility with two electron microscopes in 2018. Just a year later, I joined the Drennan lab. When I began my thesis work, Cathy asked “Would you like to do crystallography or cryo-EM?”

Eager to try something that was both novel for researchers and new to me, I chose cryo-EM.

Ancient microbes

An ancient type of microbe, archaea, also uses CODH and ACS. Without information on how these protein chains interact, we cannot understand how these proteins work together within this complex–but it’s a difficult question to answer. In total, the complex contains forty protein chains that interact with one another and adopt various conformations to perform their chemistry.

We don’t know for sure which ACS enzyme came first, the bacterial or archaeal one, but we know they are both very ancient.

Archaeal CODH has been visualized via X-ray crystallography, but that CODH was isolated from the enormous megadalton enzyme complex present in the native archaea.

A CO2 molecule, which reacts with CODH, is 44 daltons; the enzyme complex at 2.2 megadaltons is 50,000 times the size of CO2. The complex consists of several copies of CODH, ACS, and a cobalt-containing enzyme that donates the second one-carbon unit used by ACS. Due to the large and dynamic nature of the complex, it was a great candidate for visualizing with cryo-EM.

Before I joined the lab, a collaboration had been initiated between the Drennan Lab and Dr. David Grahame of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, an expert in archaeal CODH and ACS.

Just before his retirement, Grahame grew hundreds of liters of archaea and isolated approximately one gram of the enzyme complex that he provided to the Drennan Lab for structural characterization. Each cryo-EM experiment can use as little as a microgram of protein. For a structural biologist, having one gram of protein–in theory, enough for one million experiments–to work with is a dream.

Blobology

With an abundance of protein, I embarked on this project with this exciting new technique on a promising target. I prepared my cryo-EM sample and collected data at the new MIT cryo-EM facility. As I was collecting data, I could see in the images large protein complexes that appeared to be my complex of interest. I could also see some smaller proteins that were consistent with the shape of isolated CODH. When I went on to process my data, I focused on the larger protein complexes, since the structure of isolated CODH was already known.

However, when I finished processing my first dataset, I was a bit disappointed. My resolution was very low–instead of atoms, I was seeing amorphous blobs, and I had no idea which blob matched with which protein, or how the proteins fit together. Rather than post-revolution cryo-EM, I felt like I was performing the “blobology” of the past.

But the project was young, and a few failed experiments are par for the course of a PhD.

The next step was sample optimization, and luckily I had plenty of sample to work with. I tried preparing the protein in a different way, changed the protein concentration, used different additives, and scaled up my data collection.

Nothing helped. No matter what I tried, I could not move out of blobology territory. So, as one does when a project is failing, I stepped away. I worked on other projects and stopped thinking about the archaeal CODH and ACS.

A few months later, the cryo-EM facility was seeking users to try a new sample preparation instrument called the chameleon. Chameleon automates the sample preparation process and is intended to improve sample quality. With plenty of sample still to spare, I volunteered to try the instrument.

Just prior to my data collection, the facility had also installed a new software that allows data processing as it is being collected. The software uses automated processes to select proteins within your data; previously, I had only selected large protein complexes consistent with my complex of interest after the fact.

The new software is not very discriminating–but I was surprised when I looked at the results of the live processing. The processing showed that I had a protein complex in my sample that I did not expect – a complex of CODH and ACS!

This complex had just one copy of CODH and one copy of ACS, unlike the full complex that has multiple copies of each. My excitement for the project was reinvigorated. With this new target, could I leave blobology behind and finally join the resolution revolution?

After running more experiments and collecting more data and a few months of data processing, I realized that the sample contained three different states: isolated CODH, CODH with one copy of ACS, and CODH with two copies of ACS. I was able to use the Model-based Analysis of Volume Ensembles (MAVEn) tool developed by the Davis Lab at MIT to sort out these three states. When I finished the data processing, I achieved near-atomic resolution of all three states.

Through this work, for the first time, we can see what the archaeal ACS looks like. The archaeal ACS is fundamentally different from the bacterial one: a huge portion of the enzyme is missing, including part of the enzyme that makes up the active site in bacteria, leaving open the question of what the ACS active site looks like in archaea.

In our structure of archaeal ACS in complex with CODH, we were surprised to see that the active site looks almost identical to the bacterial one. This similarity is enabled by the archaeal CODH, which compensates for the missing part of ACS.

Given how similar the ACS active site environment in bacterial and archaea, we are likely getting a look at an active site that has remained conserved over billions of years of evolution.

Although the project didn’t fulfill its original promise of solving the structure of the large, dynamic protein complex, I did find intriguing insights. The tools available in 2015 would not have enabled me to achieve these results; it is clear to me that the resolution revolution is far from over, and the evolution of structural biology has been fascinating to experience. Cryo-EM has and will continue to evolve, as amazing new tools are still being developed.

Since graduating from MIT, I’ve been working at the Protein Data Bank, the data center that houses all available protein structure information. Working here gives me a front-row view of new discoveries in structural biology. I’m so excited to see where this field will go in the future.