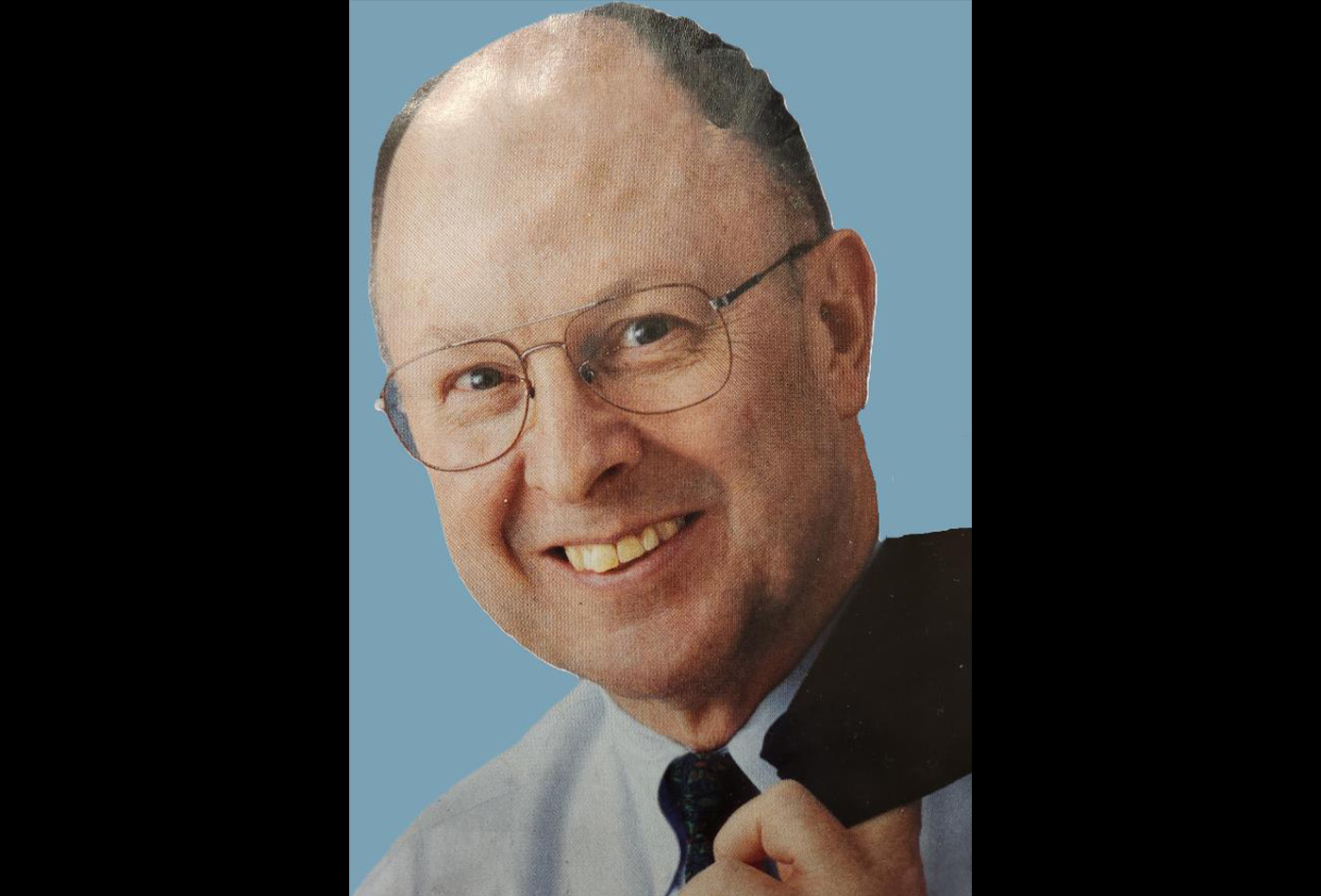

John I. Brauman (1937–2024)

Dr. John I. Brauman (SB '59), a National Medal of Science winner, passed away on August 23, 2024.

John I. Brauman, influential chemist, leader, and editor, died on 23 August at the age of 86. John made foundational contributions to the understanding of gas-phase ions, their structures, and their reactivity. He was the first to demonstrate that the order of acidity and basicity for many simple organic compounds reverses when moving from a solution to the gas phase. This discovery challenged existing assumptions about chemical behavior in different environments. John also held a variety of leadership roles in and out of academia.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on 7 September 1937, John completed his bachelor of science degree in chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1959 and earned his PhD in chemistry in 1963 from the University of California, Berkeley, under the supervision of Andrew Streitwieser. After a brief postdoctoral period with Saul Winstein at the University of California, Los Angeles, he joined the Stanford University faculty as an assistant professor. In 1969, despite initial opposition from some of his tenured colleagues, John became the first faculty member to receive tenure under the leadership of William Johnson, an impressive achievement at a time when leading American chemistry departments usually reserved tenure for already-tenured superstars hired from other institutions. John remained at Stanford until he retired in 2007.

John’s research focused on substitution reactions, in which A + BC transforms into AB + C. In cases where A is a nucleophile, meaning a molecule that donates a pair of electrons, previous research had shown that in solution, the reaction typically follows what is called an SN2 mechanism. In this process, A approaches BC from the opposite side of the leaving group C, leading to a reversal or “inversion” of the molecular structure as AB and C are formed. John discovered that in the gas phase, these substitution reactions could take a different path, proceeding through a tetrahedral transition state and bypassing the inversion process. This finding revealed that the mechanisms of chemical reactions can substantially change depending on the environment, deepening our understanding of chemical behavior.

Another major focus of John’s work was the study of electron binding to neutral molecules, a complex and crucial area of chemistry. He was the first to accurately measure the electron affinities of molecules larger than diatomic species, eventually determining these values for many important organic radicals. He developed electron photodetachment spectroscopy, which became a powerful method for studying electron affinities and the properties of neutral molecules and radicals produced by electron detachment. Additionally, he used electron photodetachment cross sections to infer the structure of negative ions and developed a theory to predict the threshold behavior for electron photodetachment from large ions. His discovery of autodetaching resonances in photodetachment spectra revealed the existence and energies of unbound electronically excited states of ions. He also identified many ions with bound electronically excited states and was the first to provide clear evidence of ions characterized as electrons bound in the field of a dipole—a phenomenon first predicted by Fermi and Teller but not previously observed.

John held numerous leadership roles throughout his career. He served as the chair of the Stanford Department of Chemistry from 1979 to 1983 and again from 1995 to 1996. He was home secretary of the National Academy of Sciences from 2003 to 2011 and a member of the board of directors for both the publisher Annual Reviews and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation. He also held positions as Stanford’s associate dean for natural sciences and associate dean of research. He was the deputy editor for physical sciences at the journal Science from 1985 to 2000 as well as chair of the journal’s senior editorial board.

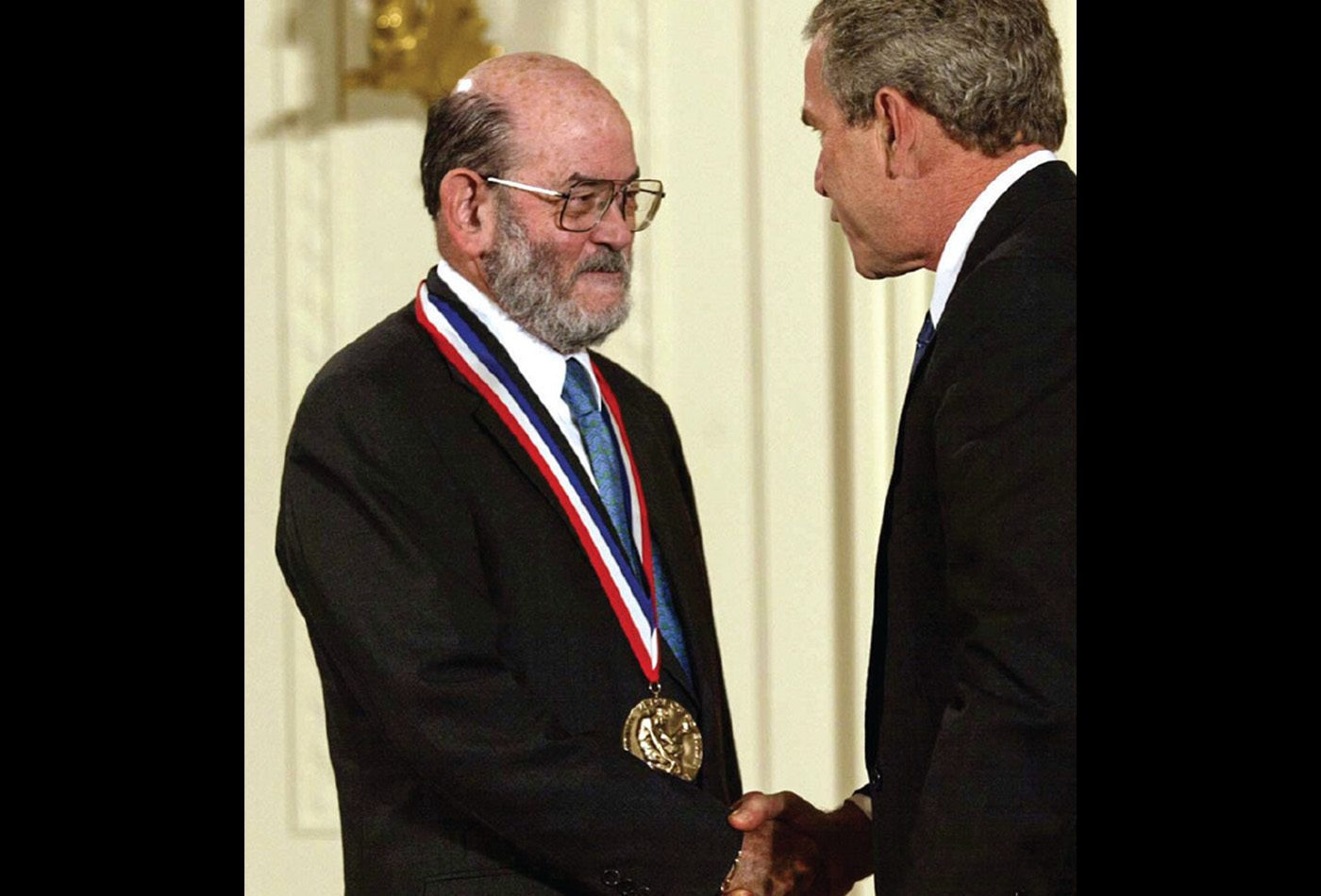

John’s achievements earned him numerous accolades, including the American Chemical Society Award in Pure Chemistry in 1973, the National Academy of Sciences Award in Chemical Sciences in 2001, and the National Medal of Science in 2002. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 2004 and received an honorary doctorate from the Scripps Research Institute in 2009.

Known for his sharp intellect and analytical mind, John often posed incisive questions that prompted committees to reconsider their decisions. His charming and sometimes mischievous nature endeared him to many, making him a sought-after adviser and mentor in both professional and personal matters. John was also an adept and inspirational teacher, whose keen insights and often humorous observations profoundly influenced the lives of many of his distinguished students.

I first met John when we were graduate students at UC Berkeley, and he was a key factor in my decision to join Stanford’s chemistry department in 1977. John played a substantial role in shaping the department and was highly valued for his ability to listen and provide insightful advice to his colleagues.

At Stanford, there was a tradition in the chemistry department called ChemWipes, where first-year graduate students performed skits that humorously poked fun at the faculty and academic life, and one year John and I were invited by the students to join in the fun. John played the banjo while we sang a parody of “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” swapping out “cowboys” for “chemists.” This moment perfectly showcased John’s ability to connect with students and his willingness to laugh at himself. It was also just one example of the way he demonstrated his deep love of music; he played a variety of stringed instruments in chamber ensembles throughout much of his life.

John is survived by his wife, chemist Sharon Brauman, whom he met during his graduate studies, and their daughter, Kate Brauman, who also became a scientist. His loss is deeply felt by everyone who had the privilege of knowing him. Anyone studying gas-phase ion chemistry today will inevitably recognize the impact of John Brauman’s contributions.

This obituary, written by Richard N. Zare, originally appeared on Science.com